Effects of UK supermarket policies on healthier food at the tills – February 2020

Confectionery, salty snacks and chocolate are often found at supermarket checkouts, which can lead to impulse purchases. Many UK supermarkets have announced policies to remove such ‘junk’ food from their checkouts. But is this having an impact on what people actually buy?

Jump to:

- Voluntary supermarket action on checkout food

- Clear policies mean healthier checkouts

- Checkout policies lead to big drop in purchases

- Parental support, but much more could be done

- Priorities for public health action

- References and resources

Brief in brief

- Eight UK supermarket chains have voluntary policies restricting ‘junk’ foods at their checkouts. Policies vary in terms of what foods and checkouts they apply to.

- Supermarkets with checkout food policies have fewer foods at their checkouts, are more likely to have no food at all, and more of the food displayed is considered healthy. Supermarkets adhere well to their policies.

- Introduction of a checkout food policy was associated with a 15-17% reduction in purchases of small packages of confectionery, chocolate and crisps.

- Parents are supportive of checkout food policies, but feel more could be done to reduce marketing in supermarkets.

Voluntary supermarket action on checkout food

Across the world, food at supermarket checkouts tends to be less healthy, and high in fat, salt or sugar. Foods at checkouts are often placed at children’s height. Both adults and children can find checkout foods hard to resist.

Some UK supermarkets have announced voluntarily policies restricting less healthy checkout food. Supermarket policies on checkout food are uncommon globally. Previous research suggests that voluntary action from food retailers rarely leads to substantial public health benefits.

CEDAR researchers contributed to a series of studies on supermarket checkout food policies in the UK. Nine supermarket chains, representing more than 90% of the UK grocery market, were included: Aldi, Asda, Co-op, Lidl, M&S, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Waitrose.

Clear policies means healthier checkouts

In April 2017, eight supermarkets had some sort of checkout food policy. Some supermarkets had very clear information on what foods could and couldn’t be displayed at checkouts. Others were vaguer – saying only, for example, ‘no sweets’. Many policies identified did not apply to all checkouts, for example self-service, kiosk and petrol station checkouts being exempt.

Three UK supermarkets have clear policies on what food can and can’t be displayed that consistently applied to all checkouts. Five supermarkets have policies that were vague about foods to be displayed or applied inconsistently to different checkouts. One supermarket has no policy.

CEDAR researchers visited 69 supermarket branches:

- In supermarkets with clear and consistent policies, 72% of checkouts had no food and 35% of foods displayed were less healthy.

- The figures in supermarkets with vague or inconsistent policies were 38% and 57%. In supermarkets with no policies they were 39% and 90%.

Checkout policies lead to big drop in purchases

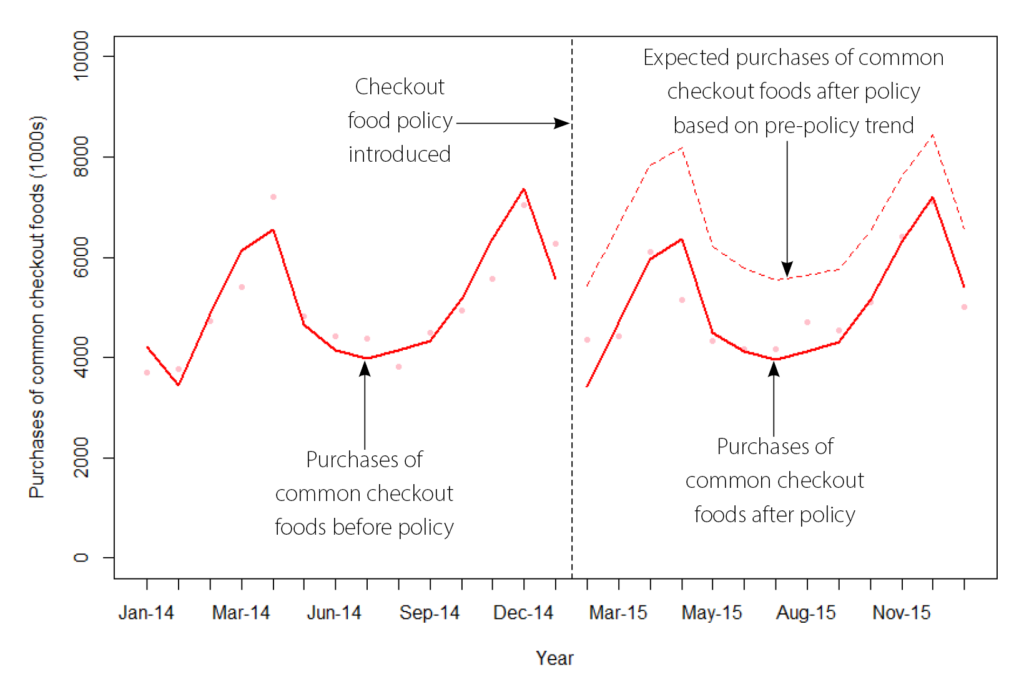

The commonest less healthy foods at UK supermarket checkouts are small packages of chocolate, confectionery and crisps. CEDAR researchers analysed data on purchases of these foods from UK supermarkets in the 12 months before and after new checkout food policies were announced.

- In the first four weeks after a new policy was announced, purchases dropped by 17% compared to the expected trend.

- One year after, there was still a 15% reduction in purchases compared to the expected trend.

- Purchases made by older households and those in the highest (as well as lowest) social grades reduced most after policies were announced.

- Older people and those in higher social grades tend to have healthier diets. So checkout food policies may not be targeting the groups who most need help to eat better.

Figure below: common checkout foods purchases in one supermarket from one year before to one year after introduction of checkout food policy.

Before the policy was introduced there are obvious seasonal trends peaking around Easter and Christmas. There is also a general increase in purchases over time.

After the policy is introduced, there is a clear reduction in purchases (solid red line) compared to what was expected based on pre-intervention trends (dashed red line).

Parental support, but much more could be done

Ninety one parents and carers took part in focus groups, talking about supermarket shopping with their children. Parents supported checkout food policies that restrict less healthy food at checkouts. Many would welcome checkouts with no food or other products.

The whole supermarket environment was considered to manipulate children. Brightly coloured packages featuring cartoon characters and placed at child’s eye height were seen as particularly problematic.

Priorities for public health action

- The healthiest checkout food displays are found in supermarkets that have policies that are clear in terms of what food can and can’t be displayed, and are applied consistently to all checkouts.

- Regulation would help create a level playing field, and support the sharing of best practice across the sector.

- Universal adoption of clear and consistent checkout food policies could lead to small improvements in dietary public health, but may not improve dietary equity.

- More should be done to reduce aggressive food marketing in supermarkets. Parents particularly criticise products that are strategically placed and packaged to attract children.

Key references and resources

- This work received funding from the Public Health Research Consortium, a Policy Research Unit, funded by the Department of Health and Social Care, UK. phrc.lshtm.ac.uk

Research

- Ejlerskov KT et al. The nature of UK supermarkets’ policies on checkout food and associations with healthfulness and type of food displayed: cross-sectional study. IJBNPA 15:52 2018 doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0684-2

- Ejlerskov KT et al. Supermarket policies on less-healthy food at checkouts: natural experimental evaluation using interrupted time series analyses of purchases. Plos Medicine 2018; doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002712

- Ejlerskov K et al. Socio-economic and age variations in response to supermarket-led checkout food policies: a repeated measures analysis. IJBNPA 15:125 2018; doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0755-4

- Ford A et al. Parents’ and carers’ awareness and perceptions of UK supermarket policies on less healthy food at checkouts: a qualitative study. Appetite 2020; doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104541

- Lam CCV et al. Voluntary policies on checkout foods and healthfulness of food displayed at, or near, supermarket checkout areas: a cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutrition, 21(18)3462-3468, 2018; doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018002501

Policy and other resources

- Restricting promotions of food and drink that is high in fat, sugar and salt. Department of Health and Social Care consultation,

January 2019. (Consultation now closed, but page links to a number of resources.) - Paying the price: New evidence on the link between price promotions, purchasing of less healthy food and drink, and overweight and obesity in Great Britain. (pdf) Cancer Research UK, March 2019

Please cite this Evidence Brief as: UKCRC Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), Evidence Brief 19 – Effects of UK supermarket policies on healthier food at the tills – February 2020. www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/resources/policy-resources/evidence-briefs/eb-checking-out-checkout-food/

MRC Epidemiology Unit

MRC Epidemiology Unit