Not all sedentary behaviours are the same when it comes to mental health – April 2022

Excessive sedentary behaviour has been linked with poor mental health, including depression. But while much of the research on this area treats all sedentary behaviours as one activity, it may be that the importance of what we do when we sit has been overlooked.

Jump to:

- Separate sittings

- From adolescence to adulthood

- Possible pathways: BMI and self-rated health

- More important for girls

- Priorities for future research

- Priorities for public health action

- References and resources

Brief in brief

- Excessive sedentary behaviour has been linked with poor mental health, including depression.

- Sedentary behaviour includes a wide range of behaviours, both mentally active and passive, and they have different associations with mental health indicators.

- Promotion of better mental health should focus on reducing mentally-passive sedentary behaviours.

- Research should find new ways to collect data that better distinguish between different types of sedentary behaviours.

Separate sittings

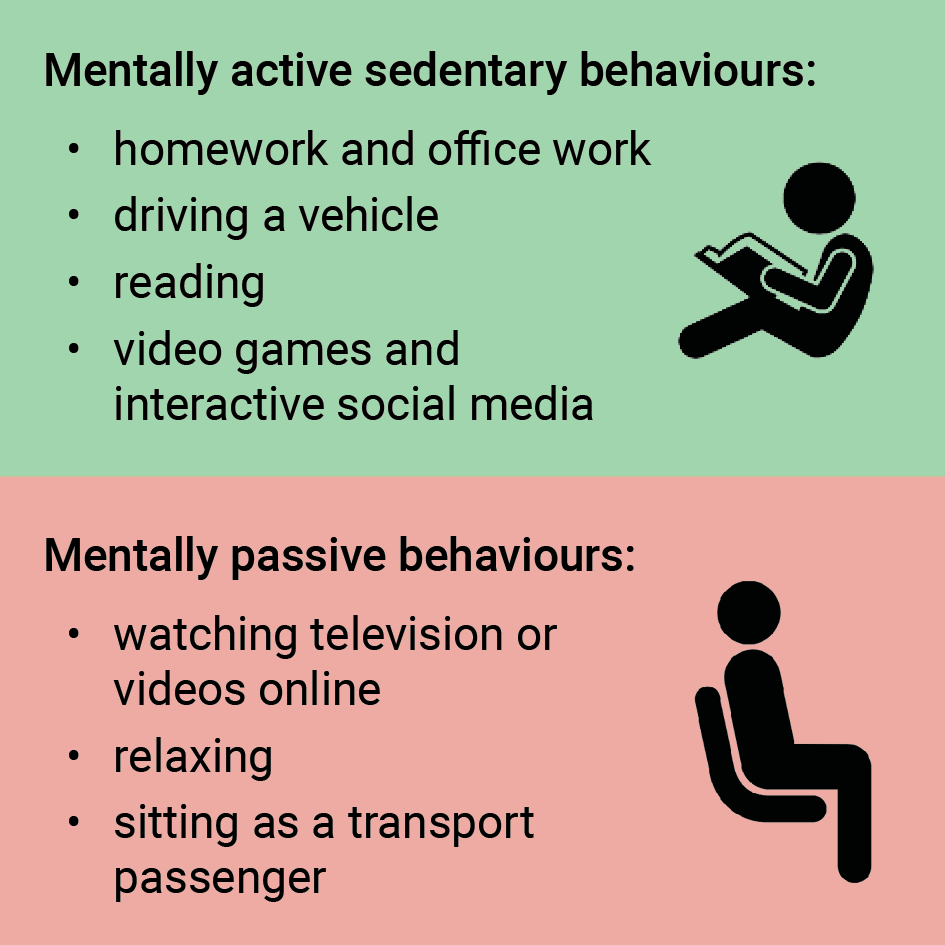

Sedentary behaviour includes a range of activities: reading, gaming, home and office work, and travelling in vehicles. Each of these activities have distinct characteristics. How we classify and measure different sedentary behaviours is important to understanding their impact.

Some studies have attempted to group these behaviours by the way we divide our days – for instance, in leisure, travelling, at work and so on. However, within ‘leisure’, some behaviours – such as TV viewing – are associated with developing depressive symptoms. Other behaviours – such as computer use in adults and video games in adolescents – are not associated with depression, and can even be protective.

When it comes to mental health, therefore, a more helpful classification is one based on the level of mental activity or passivity during the time spent sitting.

From adolescence to adulthood

Data from the 1970 British Cohort Study showed that a higher level of mentally-passive sedentary behaviour during adolescence (at 16 years) was associated with elevated psychological distress during adulthood (at 42 years). There was no link between more mentally-active sedentary behaviour and later psychological distress.

And data from the Millennium Cohort Study showed that mentally-passive sedentary behaviour during early adolescence (11 years) was associated with higher depressive symptoms in later adolescence (at 15 years). Mentally-active sedentary behaviour at 11 was not associated with later depressive symptoms.

Possible pathways: BMI and self-rated health

Research from adults and adolescents using the 1970 British Cohort Study and the Millennium Cohort Study also sought to investigate possible factors that could explain at least part of the harmful associations between mentally-passive sedentary behaviour and depressive symptoms.

In adolescents, Body Mass Index (BMI) partly explained the association, as did self-rated health in adults. In other words, this suggests that mentally-passive sedentary behaviour may lead to higher BMI (for adolescents) and lower self-rated health (for adults). This in turn could lead to higher depressive symptoms among adolescents and psychological distress among adults.

More important for girls

Research has found gender differences for the association between sedentary behaviour and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Mentally-passive sedentary behaviour is associated with depressive symptoms among girls, but not among boys.

This finding may indicate that other non-sedentary behaviours (e.g. physical activity) can be more important in the context of risks and protective factors for depressive symptoms among boys.

Priorities for future research

- Analyses of the association between sedentary behaviour and mental health outcomes should consider the different types of sedentary behaviour rather than just a single indicator of total sitting time.

- Currently, most commonly used questionnaires only include overall sitting time. This means the distinct associations of different behaviours with mental health outcomes may be underestimated.

- Research should therefore incorporate questionnaires that enable a distinction to be made between different types of sedentary behaviour.

Priorities for public health action

- Interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour should focus on behaviours that impact mental health. This may involve replacing mentally-passive sedentary behaviour with physical activity or with mentally-active sedentary behaviour.

- Increases in screen time caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are a particular cause of parental anxiety. However, refocusing screen time on mentally active activities may be more productive than attempts to place strict limits on total screen time.

- Interventions that target associated health factors (such as BMI and self-rated health) may also be helpful in reducing the connection between sedentary behaviour and poor mental health outcomes.

References and resources

Core references

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. 2020.

www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 - Associations between mentally-passive and mentally-active sedentary behaviours during adolescence and psychological distress during adulthood. André O.Werneck et al. Preventive Medicine, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106436

- Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. van Sluijs, E et al. The Lancet, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01259-9

- Association of mentally-active and mentally-passive sedentary behaviour with depressive symptoms among adolescents. André O. Werneck et al. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.004

Other references

- Sedentary Behaviour Council Global Monitoring Initiative Working Group. Worldwide surveillance of self-reported sitting time: a scoping review. Mclaughlin M et al, Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01008-4 - Sedentary behaviors and risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Huang, Y et al. Translational psychiatry, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0715-z

- The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. Hoare, E, Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2016 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0432-4

- Prospective relationships of adolescents’ screen-based sedentary behaviour with depressive symptoms: the Millennium Cohort Study. Kandola, A et al, Psychological medicine, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000258 - Passive Versus Mentally Active Sedentary Behaviors and Depression. Hallgren, M et al, Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000211

- Cross-sectional and prospective relationships of passive and mentally active sedentary behaviours and physical activity with depression. Hallgren, M et al, British Journal of Psychiatry, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.60

- Distinct associations of different sedentary behaviors with health-related attributes among older adults. Kikuchi, H et al, Preventive medicine 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.011

MRC Epidemiology Unit

MRC Epidemiology Unit