In September 2021, the UK government and devolved administrations announced the decision to introduce mandatory fortification of UK non-wholemeal flour with folic acid, the synthetic form of the vitamin folate (also known as vitamin B9). Folate is necessary for DNA synthesis and replication required for normal cell development and growth. The main dietary sources of folate are green leafy vegetables, pulses, and foods such as breakfast cereals that are fortified with folic acid.

In adults and children folate deficiency may lead to megaloblastic anaemia, a form of anaemia where underdeveloped red blood cells are larger than normal, and inadequate folate is a risk factor for neural tube defects and other poor health outcomes during foetal development. It is estimated that approximately 1,000 pregnancies are affected by neural tube defects each year in the UK.[i] Therefore it is particularly important that women of child bearing age (16-49 years) have sufficient folate intakes, and it is recommended by the UK government that women who are pregnant or who could become pregnant take a 400μg folic acid supplement daily until the 12th week of pregnancy.

The National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS RP) has been running since 2008 and is a continuous, cross-sectional survey designed to assess nutrient intake and nutritional status of the general population in the UK. It is currently carried out by the MRC Epidemiology Unit and NatCen Social Research, and is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care and the Food Standards Agency. The NDNS RP and earlier NDNS surveys have been major contributors to the evidence base underpinning the recent decision to mandate the addition of folic acid to non-wholemeal wheat flour across the UK.

Monitoring the decrease in folate intake in the UK

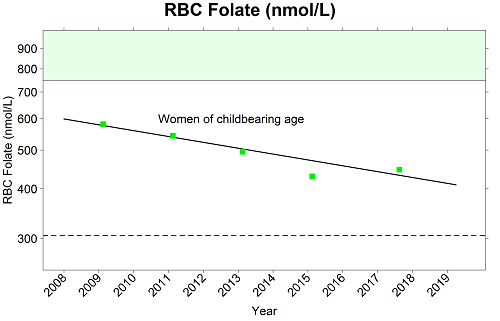

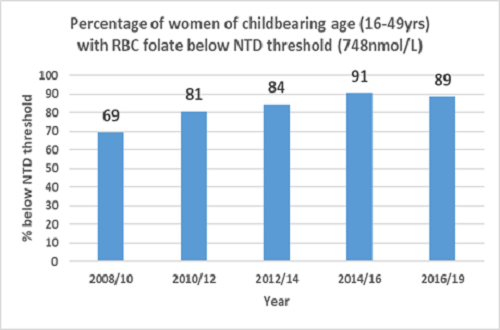

Data from the most recent NDNS RP report (2008 – 2019) shows that folate concentrations in the blood have, on average, decreased over the 11 years, including in women of child bearing age. NDNS RP figures show that the proportion of women of childbearing age in the UK with red blood cell (RBC) folate concentrations below the threshold (748nmol/L) for minimising risk of neural tube defects is substantial, with an overall increase from almost 70% of women to 90% over the 11 years.

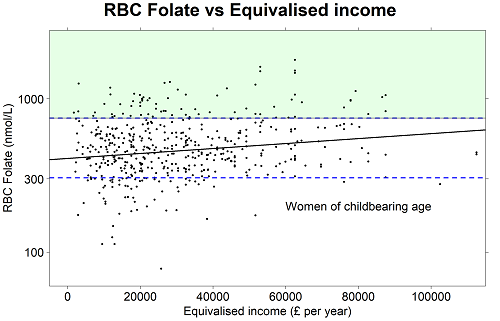

NDNS RP data also show that RBC folate concentration increases with increasing income,[ii] meaning that women from households on lower incomes are less likely to be consuming enough folate through their diet or by taking folic acid supplements.

How NDNS data supported recommendations to improve UK folate status

In 2006, 2009 and most recently in 2017, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recommended the mandatory folic acid fortification of flour to improve the folate status of women most at risk of NTD-affected pregnancies.[iii] [iv] [v] SACN have used NDNS for scientific evidence relating to UK folate intakes and sources in the diet. These data, along with the folate content of foods from the NDNS Nutrient Databank[vi] and blood folate status, were used to model the impact of different scenarios of folic acid fortification on folate intakes in the UK and reduction of risk of NTDs.[vii]

Over the last 20 years, around 90 countries have introduced mandatory fortification of wheat and/or maize flour.[viii] Whilst data from some of these countries has demonstrated improvements in folate status and reductions in neural tube defects,[ix] [x] few countries have nationally-representative data in women of childbearing age from both pre- and post-fortification periods. Additionally, variation in analytical methods and the use of different cut-offs for deficiency and insufficiency complicate interpretation. Representative data from women of childbearing age in the United States showed that post-fortification population RBC folate levels were 1.5 times pre-fortification levels, and demonstrated an overall reduction of 28% in neural tube defect prevalence between the pre- and post-fortification periods. [xi] [xii]

Looking to the future

Major strengths of the UK NDNS RP include regular collection of detailed dietary intake and folate status data on a nationally representative population sample using robust and reliable methods of data and sample collection. The NDNS RP uses two methods to assess folate status: (1) the RBC folate microbiologic assay recommended by the World Health Organization to indicate long-term folate status [xiii] and (2) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to measure serum folate status, including the different folate forms that are of particular interest in the context of folic acid fortification. This assessment is led by the Unit’s Nutritional Biomarker Laboratory, which is located on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus.

The data from the NDNS RP provided strong evidence to support folic acid fortification in the UK, and will now give researchers and policy makers the key information needed to evaluate this new policy once it is implemented.

Professor Ann Prentice OBE, Honorary Senior Visiting Fellow, MRC Epidemiology Unit, commented:

The decision by the UK government and devolved administrations to mandate folate fortification of UK flour is an important step forward in tackling the high prevalence of poor folate status in our nation. This is particularly acute in women of childbearing age but is also of concern for the general population.

I have been closely involved with NDNS since the early 1990s when the measurement of folate biomarkers was first introduced, and I was also a member and subsequent Chair of SACN that provided the evidence-based recommendations to the policy makers. I have witnessed first-hand the rigour of both the NDNS RP assessments and the scientific judgements leading to this decision.

The MRC Epidemiology Unit, through its current role as scientific lead for the NDNS RP and through those senior scientists who are currently members of SACN (Professor Ken Ong and Dr Jean Adams), will continue to play an important and active role in supporting the UK governments to evaluate the success of this initiative to improve folate status in the UK.”

References

[i]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/808698/folic-acid-impact-assessment.pdf

[ii] National Diet and Nutrition Survey Years 1 to 9 of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009 – 2016/2017): Time trend and income analyses. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-time-trend-and-income-analyses-for-years-1-to-9

[iii] The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Folate and disease prevention. London: The Stationery Office; 2006. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-folate-and-disease-prevention-report

[iv] The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Report to CMO on folic acid and colorectal cancer risk. London: The Stationery Office; 2009. Available from:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-report-to-cmo-on-folic-acid-and-colorectal-cancer-risk

[v] The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Update on Folic Acid. London: The Stationery Office; 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/folic-acid-updated-sacn-recommendations

[vi] National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 9 to 11 (combined) 2016/2017 – 2018/2019). Appendix A. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019

[vii] Food Standards Scotland. Stochastic modelling to estimate the potential impact of fortification of flour with folic acid in the UK. 2017. Available from: https://www.foodstandards.gov.scot/publications-and-research/publications/stochastic-modelling-to-estimate-the-potential-impact-of-fortification-of-f

[viii] https://fortificationdata.org/availability-of-data-on-health-status-before-and-after-mandatory-fortification/

[ix] Keats EC, Neufeld LM, Garrett GS, Mbuya MNN, Bhutta ZA. Improved micronutrient status and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries following large-scale fortification: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019 Jun 1;109(6):1696-1708. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz023

[x] Atta CA, Fiest KM, Frolkis AD, Jette N, Pringsheim T, St Germaine-Smith C, Rajapakse T, Kaplan GG, Metcalfe A. Global Birth Prevalence of Spina Bifida by Folic Acid Fortification Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Public Health. 2016 Jan;106(1):e24-34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302902

[xi] Pfeiffer CM, Hughes JP, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, Berry RJ, Zhang M, Yetley EA, Rader JI, Sempos CT, Johnson CL. Estimation of trends in serum and RBC folate in the U.S. population from pre- to postfortification using assay-adjusted data from the NHANES 1988-2010. J Nutr. 2012 May;142(5):886-93. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.156919

[xii] Williams J, Mai CT, Mulinare J, Isenburg J, Flood TJ, Ethen M, Frohnert B, Kirby RS. Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification—United States, 1995–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(1):1–5

[xiii] WHO. Guideline: Optimal serum and red blood cell folate concentrations in women of reproductive age for prevention of neural tube defects. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

MRC Epidemiology Unit

MRC Epidemiology Unit