Dr Oliver Mytton was selected as a finalist for the 2019/2020 The Bennett Prospect Prize for Public Policy for this essay on how a Healthy Food Act could improve the health of the UK.

The Bennett Prospect Prize for Public Policy is awarded by the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge and is held in partnership with Prospect Magazine. The goal is to encourage early career researchers and policy professionals to explore creative and generative solutions to a pressing public policy question of our age. In 2019/2020 they asked entrants the question ‘Which single public health intervention would be most effective in the UK?’

The Healthy Food Act

Emma is eleven years old. She is 1.4 metres tall and weighs 55 kg. This means she has obesity.

Emma is not unusual. She has a sweet tooth and does not like vegetables. She eats chocolate bars most days, and regularly goes to the local chicken shop with her friends. She is largely a happy girl, although she has been bullied about her weight.

Emma also has asthma. Because of her obesity, she has more frequent and severe asthma attacks. Fat has started to build up in her liver. While this does not cause any problems for her, she does need to see a liver specialist for monitoring.

Even with specialist help, her obesity will probably persist into adult life. It may then cause a range of problems: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, some cancers, joint and muscle problems, reduced fertility, depression and liver disease. This will not only reduce her life expectancy, by as much as six years, but also her years lived in good health, by as much as 15 years.[1]

Emma is also likely to earn less than someone who is a healthy weight. On average an adolescent girl with obesity earns £100,000 less across a lifetime.[2]

Why does Emma have obesity?

Emma’s parents find it hard to manage Emma’s weight. Unhealthy food options permeate into many areas of their life. It is not just takeaway outlets that offer unhealthy food options, but many other shops too, newsagents, petrol stations and clothes shops; as well as other places, leisure centres, cinemas, bus and rail stations. Shops know what tricks work to get people to buy more: placing confectionary near the checkouts, using cartoon characters that directly appeal to children, placing sweets at children’s eye level. The unhealthy food options flow freely, and Emma’s parents are drowning.

It is the unhealthy foods and brands that burn brightly in Emma’s mind. Companies compete hard to place their products centre stage, buying up prime time slots on family shows and billboards near schools. Increasingly companies can advertise directly to children online, making use of ‘advergames’ (free to use computer game used to market unhealthy food). Sponsorship of major sporting events, children’s sporting activities and festivals may be used to create brand recognition and a positive aura around unhealthy products.

The advertising and messaging for healthy food is drowned out by that for unhealthy foods. In 2017, £302 million was spent promoting sugary drinks and snacks in the UK, compared to £16 million spent promoting fruit and vegetables.[3] Young minds are much less able to recognise, let alone understand and resist advertising. Is it any wonder that Emma and her friends are constantly seeking sweet treats?

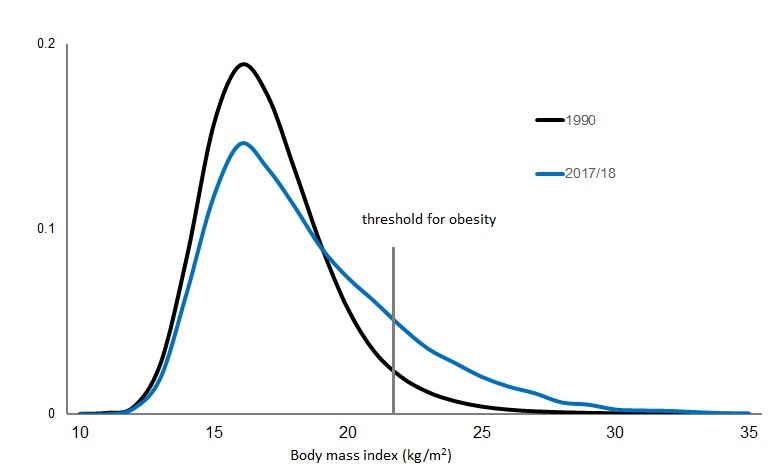

It may be common to attribute Emma’s obesity to genes or poor parenting, but as Emma’s story illustrates there have been profound changes in the type, availability and marketing of food, which make it much harder to eat healthily and maintain a normal weight. Sadly, Emma is no longer unusual. In 1990, only one girl out of 100 was like Emma. Today for every 100 girls aged 11 years, 15 will have obesity like Emma.

The increasing number of people with obesity is an indicator of profound and widespread changes in food available . Everyone is exposed to these changes and pressures. It is affecting nearly everybody’s diet and health. Many people who are a healthy weight will be consuming a poor diet that is affecting their health. Overall, only 13% of adults meet the recommended intake of sugar, 9% the recommended intake of fibre, and 17% the recommended five daily portions of fruit and vegetables.[4,5] More needs to be done to ensure we all have the opportunity to eat healthy food.

Source: 2017/18 National Child Measurement Programme; 1990 based on UK growth standards.

Regulation

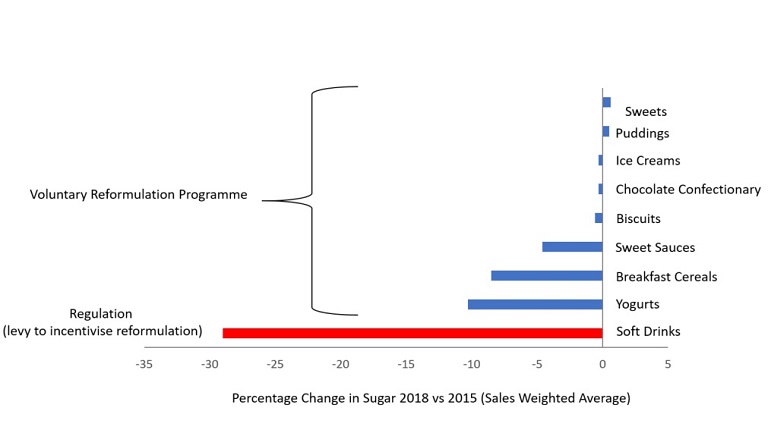

In 2011 the UK government embarked on an ambitious and voluntary ‘responsibility deal’ with the food industry, asking the industry to do more to ensure people had healthy options. Despite good engagement from large parts of the industry, it failed.[6] In contrast, the Soft Drinks Industry Levy, a tax on the manufacturers of sugary drinks based on the sugar content of their products, has led to significant change. The levy was announced in 2016 and introduced in 2018. Between 2015 and 2018, the amount of sugar in soft drinks fell by 29% compared to minimal changes for other products containing sugar, which were only subject to a voluntary programme (Figure 2).[7]

Food production, marketing and sale is highly regulated. But the focus of this regulation is ‘food safety’, preventing contamination of food with microbes or harmful toxins. Today, food poisoning causes 500 deaths each year,[8] or 0.1% of all deaths, in the UK. In contrast, poor quality diets contribute to many of the major, and often preventable, causes of death and disability in the UK, such as heart disease, stroke, some cancers, dementia and type 2 diabetes, as well as obesity. Taken together poor diet accounts for 15% of all deaths in the UK, 150 times the burden of food poisoning, and 8% of disability adjusted life years lost.[9] This is greater burden of illness than smoking, or any other single risk factor.[10]

Source: Sugar Reduction Report on Progress 2015 to 2018, Public Health England.[7] A levy on soft drinks was announced in 2016, and implemented in April 2018. From 2016 onwards Public Health England has led a voluntary programme of sugar reduction focused on the main contributors of sugar to people’s diet.

The Healthy Food Act

There is growing evidence linking certain foods, such as sugary drinks, sweet desserts and crisps, to poor health.[11] As well as growing evidence linking the retail and marketing tactics to excess consumption of these products. A new act is needed, the Healthy Food Act, that mirrors the Food Safety Act. Changes in the law have been a very effective means to improve the public’s health. In the UK, smoke free legislation, the soft drinks industry levy and minimum unit pricing on alcohol, all examples of legislative actions to achieve public health goals, were recently cited as amongst the top five public health achievement of the 21st century.[12]

Like the Clean Air Act (1956) and the Food Safety Act (1990), the Act should seek to catalyse widespread change and include a broad suite of measures. When trying to increase sales, food companies focus on the four ‘Ps’ of marketing (product, price, place and promotion). Companies seek synergies between these approaches, for example placing discounted products at the checkout. If one approach is blocked, for example if price discounts was restricted, they might compensate by making greater use of other approaches, using advertising and placing products on the end of isle. To be effective, the Act needs to address all four aspects simultaneously.

Such an approach would avoid the unhelpful focus on single measures. Focusing on single measures, reflecting a reductionist approach to science, may be ineffective and result in slow progress. It is akin to focusing on a single sandbag, when the flood can only be held back by a wall of sandbags. Likewise, the most effective intervention for heart attack is a timely referral to a specialist hospital (enabling assessment, treatment and rehabilitation). Reducing the question to a comparison of aspirin, clot busting drugs or surgery to open a blocked artery, can be unhelpful.

A strong set of measures across the four Ps will send a strong signal to the food industry. Currently, it is relatively easy to make money from selling unhealthy food, yet hard to make money from selling healthy food. The Act should change that balance, so that businesses that act to support the health of their customers are incentivised, not penalised. A broad set of measures will have greater credibility with the public. They recognise that individual measures alone will not be enough.

Product

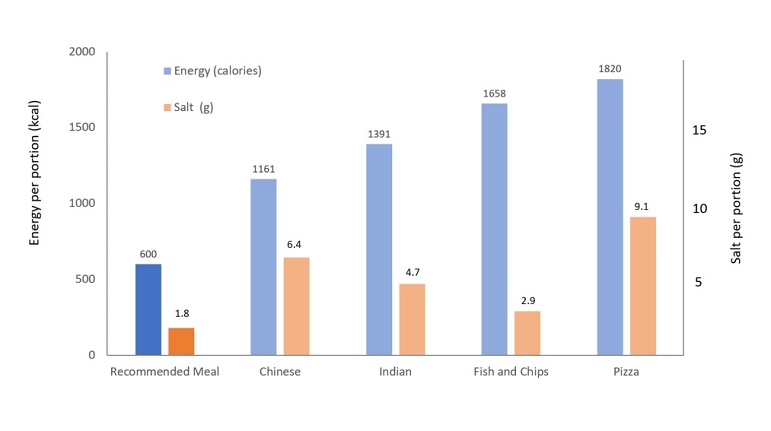

Large portion sizes encourage people to consume more food.[13] Portion sizes have increased overtime.[14] For example, the average pizza sold in a supermarket has increased from 200g in 1990 to 305g in 2019.[15] Many portion sizes, particularly those sold in the out of home sector far exceed recommended levels of salt and calories (Figure 3).

Source: Based on a sample of 489 takeaway meals in Liverpool, 2014.[16] Public Health England recommend 600kcal for a meal. Recommended salt intake is less than 6g per person, which equates to 1.8g for a meal.

Proposals by the previous government to introduce calorie labelling for the out of home sector were likely to exclude small businesses.[17] They should not be excluded. Most takeaway outlets are small businesses and not part of a major chain. McDonalds, one of the major fast food outlets in the UK has 1250 franchise in the UK,[18] only 2% of the 60,000 takeaway outlets in the UK. The introduction of standard sized boxes for takeaway outlets could be a means to introduce an effective calorie cap as well as provide portion standardisation to give indicative calorie information for small businesses.[19]

Takeaways are more commonly found in more deprived neighbourhoods.[20] Effective action on portion sizes can be expected to reduce health inequalities.

There should be consistent and minimum standards for the nutritional labelling of food (e.g. standardised traffic light labels) and calorie labelling. Calorie labelling and nutrition labelling may be relatively weak tools to change individual’s purchasing behaviour.[21] Only a minority of customers read, process, understand and use the information. However, they do appear to be effective at encouraging manufacturers to reformulate their products.[22] Their adoption outside the home, would also permit much greater monitoring and understanding of practices outside the home.

There should also be clear and standardised guidance on portion sizes for products, such as breakfast cereals that are sold in large packets. Leaving the European Union, now gives the UK the freedom to introduce uniform standards.

Just as food safety is a mandatory part of the training of chefs and others working in the food industry, the act should ensure that this extended to fully consider the role of food on human health.

Price

The use of price promotions, such as buy two for the price of one, has been shown to increase overall purchasing of food.[23] Price promotions are used much more heavily in the UK than other European countries. Around 40% of food purchased to consume at home is on a price promotion, compared with 20% in other European countries.[24] Germany and Denmark have prohibited price promotions for many years, instead favouring fixed unit pricing.[25] This is seen as fair and is popular with customers.

Other pricing structures also encourage people to overconsume food. Takeaway meals often encourage customers to buy larger portions by making larger meals look like better value, an additional 30% for a marginal increase in cost. Fixed unit pricing should be standard, so that a portion that is 30% bigger costs 30% more.

Placement

The placement of unhealthy products near checkouts should be prohibited in both food and non-food stores, like clothes shops and petrol stations. In supermarkets, these restrictions have been shown to successfully reduce the purchasing of these products.[26]

In shops the sale of food should be conditional on having a balanced display of all foods, with a minimum amount of shelf space being taken up by healthy food items, such as nuts, fruits, vegetables.

The approach is being trialled in shops within NHS premises. This will ensure greater access to healthy options but would also be a major opportunity and incentive for business to innovate to provide healthy options.

Promotion

Promotion or advertising of unhealthy food has been shown to increase awareness of, preferences for, purchasing and consumption of unhealthy food.[27] For children a direct consequence of this exposure is eating more unhealthy food. Each additional advert seen, on average prompts a child to eat six more calories of food.[28,29] Whilst that may sound small, over time and collectively, it is estimated that this contributes to an additional 55,000 children with obesity (6.4% of all children with obesity).[29]

Restricting advertising, particularly television advertising of unhealthy food to after the 9pm watershed, has significant potential to reduce these harms.[29] However, it may be relatively easy for advertisers to move these adverts online to circumvent these regulations. There is strong public support for greater restrictions on the advertising of unhealthy food, particularly when targeted at children.[15]

Children living in more deprived neighbourhoods tend to be more exposed to unhealthy food advertising on television. My work suggests that reductions in childhood obesity would be twice as great amongst children living in most deprived households compared to those in the least deprived.[29]

Lessons can be learnt from restrictions on tobacco advertising and sponsorship.[30] As restrictions were introduced tobacco, manufacturers looked to new routes to promote their products, such as sports sponsorship. Full restrictions took time. Television advertising of tobacco was banned in the UK in 1965, but a full ban on all advertising and sponsorship did not come into effect until 2005. The Act should bring in a set of advertising restrictions that apply across all media, as well as incorporating sporting and cultural events.

The current tax rebate on food advertising should be reviewed (advertising is currently treated as a business cost so can be offset against tax) for unhealthy food and should remain for advertising of healthy food.

Implementation

Like smoke free legislation some aspects of this legislation may be self-policing. Others, such as further television advertising restrictions on unhealthy foods, represent an extension of existing approaches so would have a minimal additional burden. Some of the legislation will require enforcement.

Every local authority employs a team of environmental health officers, who are responsible for the inspection of food premises to ensure food safety. Given the changing burden of disease, their role should be enhanced to include the issues outlined here. As with alcohol, any premise selling unhealthy food would have to formally apply for a license to the local authority. A system of licensing could be used to generate the revenue necessary to fund enforcement and might act as a barrier for non-food shops to sell food.

Many local authorities want to restrict the opening of new takeaway outlets,[31] but the current National Planning Framework is often too weak to enable them to do this. It is also applied inconsistently. The Act should give local authorities enhanced powers to control planning. Currently, the burden of proof, to show harm from a new takeaway outlet, is placed on the local authority. The burden of proof should be on the applicant to show that their restaurant will not cause additional harm.

Conclusion

The food available and how it is marketed is shaping what people eat and adversely affecting their health. This affects nearly everybody. A Healthy Food Act should be introduced to set minimum standards for how food is sold and marketed. This is important not just for Emma’s health, but for everybody’s health. The Act needs to be broad based to be effective. Done correctly, making the healthy option the normal option rather than merely providing information, it can also contribute to reducing the gap in health between the most and least affluent. Done correctly it will incentivise businesses to produce and market healthy foods.

References

- Grover SA, Kaouache M, Rempel P, et al. Years of life lost and healthy life-years lost from diabetes and cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese people: a modelling study. lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:114–22. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70229-3

- Hamilton D, Dee A, Perry IJ. The lifetime costs of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2018;19:452–63. doi:10.1111/obr.12649

- The Food Foundation. The Broken Plate. 2019.

- MRC Human Nutrition Unit, National Centre for Social Research. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 5 and 6 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2012/2013 – 2013/2014). 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/551352/NDNS_Y5_6_UK_Main_Text.pdf

- MRC Human Nutrition Unit, National Centre for Social Research. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 7 and 8 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015 to 2015/2016). 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/699241/NDNS_results_years_7_and_8.pdf

- Knai C, Petticrew M, Douglas N, et al. The Public Health Responsibility Deal: Using a Systems-Level Analysis to Understand the Lack of Impact on Alcohol, Food, Physical Activity, and Workplace Health Sub-Systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2895. doi:10.3390/ijerph15122895

- Niblett P, Coyle N, Little E, et al. Sugar reduction: progress between 2015 and 2018. London: 2019.

- Wadge A. Annual Report of the Chief Scientist 2012/13 Safer food for the nation. 2013.

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019;393:1958–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

- Newton JN, Briggs ADM, Murray CJL, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2257–74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00195-6

- Mozaffarian D. Dietary and Policy Priorities for Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and Obesity: A Comprehensive Review. Circulation Published Online First: 8 January 2016. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585

- Royal Society for Public Health. Top 20 public health achievements of the 21st century. 2019.https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/top-20-public-health-achievements-of-the-21st-century.html (accessed 30 Dec2019).

- Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, et al. Portion, package or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;:CD011045. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011045.pub2

- British Heart Foundation. Portion Distortion. 2013.

- Davies S. Time to Solve Childhood Obesity. London: 2019.

- Jaworowska A, M. Blackham T, Long R, et al. Nutritional composition of takeaway food in the UK. Nutr Food Sci 2014;44:414–30. doi:10.1108/NFS-08-2013-0093

- Department for Health. Childhood obesity: a plan for action, chapter 2. London: 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action-chapter-2

- 18 McDonalds. Become a franchisee. https://www.mcdonalds.co.uk/ukhome/People/Franchising.html/ (accessed 30 Dec2019).

- Goffe L, Hillier-Brown F, Hildred N, et al. Feasibility of working with a wholesale supplier to co-design and test acceptability of an intervention to promote smaller portions: an uncontrolled before-and-after study in British Fish & Chip shops. BMJ Open 2019;9:e023441. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023441

- Maguire ER, Burgoine T, Monsivais P. Area deprivation and the food environment over time: A repeated cross-sectional study on takeaway outlet density and supermarket presence in Norfolk, UK, 1990-2008. Health Place 2015;33:142–7. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.02.012

- Long MW, Tobias DK, Cradock AL, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Impact of Restaurant Menu Calorie Labeling. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e11–24. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302570

- Wellard-Cole L, Goldsbury D, Havill M, et al. Monitoring the changes to the nutrient composition of fast foods following the introduction of menu labelling in New South Wales, Australia: an observational study. Public Health Nutr 2017;21:1–6. doi:10.1017/S1368980017003706

- Nakamura R, Suhrcke M, Jebb SA, et al. Price promotions on healthier compared with less healthy foods: a hierarchical regression analysis of the impact on sales and social patterning of responses to promotions in Great Britain. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 808–16 (2015. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:808–16. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.094227

- Smithson M, Kirk J, Capelin C. Sugar Reduction: The evidence for action Annexe 4: An analysis of the role of price promotions on the household purchases of food and drinks high in sugar. London: 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/470175/Annexe_4._Analysis_of_price_promotions.pdf

- British and Irish Parliamentary Assembly. Childhood Obesity Follow-up. 2018. http://www.britishirish.org/assets/10.06.18-Childhood-obesity-follow-up-BIPA-report-for-members.pdf

- Ejlerskov KT, Sharp SJ, Stead M, et al. Supermarket policies on less-healthy food at checkouts: Natural experimental evaluation using interrupted time series analyses of purchases. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002712. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002712

- Kelly B, King MPsy L, Chapman Mnd K, et al. A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e86-95. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302476

- Russell SJ, Croker H, Viner RM. The effect of screen advertising on children’s dietary intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev Published Online First: 21 December 2018. doi:10.1111/obr.12812

- Mytton OT, Boyland E, Adams J, et al. Quantifying the potential health impact of restricting less-healthy food and beverage advertising on UK television between 0530 and 2100: a modelling study. Under Rev

- Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q 2009;87:259–94. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x

- Keeble M, Burgoine T, White M, et al. How does local government use the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets? A census of current practice in England using document review. Health Place 2019;57:171–8. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.010

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011;378:804–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1

MRC Epidemiology Unit

MRC Epidemiology Unit