A new study published by scientists from the Unit and Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR) in BMJ Open has found that the influence of better walking and cycling infrastructure on unconscious pathways may be more powerful in driving behaviour change than any explicit conscious change in perceptions of the physical and social environment.

Those who support active travel have long campaigned for better infrastructure, and many local authorities are making changes to urban environments to promote both walking and cycling. However, few scientific studies have evaluated the effects of changing the environment to provide evidence that designing healthier cities actually does lead to changes in health behaviours.

In an environment of limited resources, this isn’t just an academic question: should Councils and campaigners focus on improving infrastructure, or should resources be reserved for campaigns to educate and change perceptions about the benefits of being active through travel?

In July 2014, one of the few studies from the UK which assessed the effects of new walking and cycling routes published findings that showed increases in walking, cycling and physical activity two years after the construction of new routes. This latest research builds on this by exploring some of the reasons behind this change. Researchers used the same questionnaire data to explore whether the effects of new walking and cycling routes could be explained by reported improvements in conditions for walking and cycling.

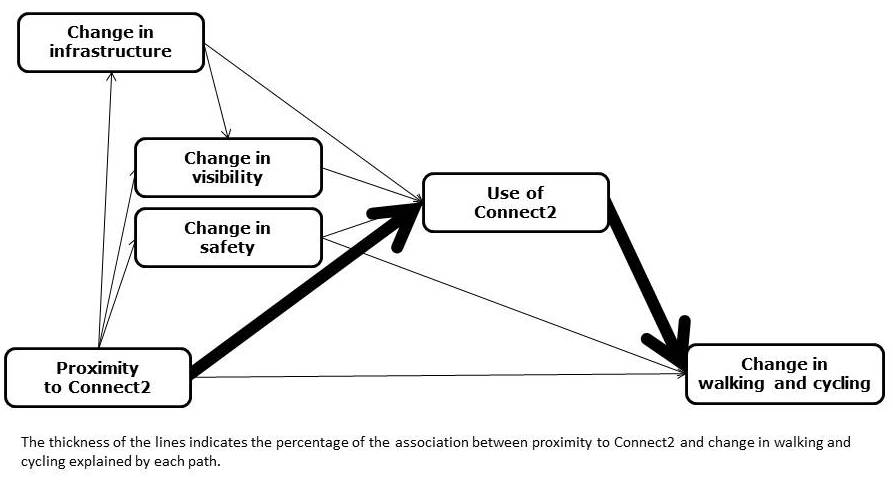

The researchers surveyed adults living within 5 km of new walking and cycling infrastructure in Cardiff, Kenilworth and Southampton, part of the Connect2 initiative run by Sustrans to develop new walking and cycle routes in 79 communities around the UK. They used a statistical method called path analysis to assess the magnitude and significance of the hypothesised causal relationships between the sets of variables. They found that although residents perceptions of pleasantness, crime, lighting or safety improved over 2 years, these didn’t explain their changes in walking, cycling and physical activity. In fact 90% of the changes could be explained by a simple causal pathway driven by the use of the new routes, whilst changes in cognitive perceptions of the environment explained only a very small proportion.

This suggests that the physical improvement of the environment itself was the key to the effectiveness of the intervention. Seeking to change people’s perceptions may therefore be of limited value. This might lend weight to the notion of more automatic unconscious pathways suggesting that behaviour can be promoted by changing environmental cues without explicitly encouraging behaviour, sometimes referred to as ‘nudging’.There was some evidence that the programme of new infrastructure was successful in influencing these characteristics of the environment, and that these changes may have contributed to people taking up the opportunity to use the new infrastructure. Other work using the interviews with local authorities, cycling groups and building contractors suggested that the visibility, scale and design of the schemes and the contrast they presented with existing infrastructure may have influenced their use.

Reference:

Jenna Panter, David Ogilvie on behalf of the iConnect consortium Theorising and testing environmental pathways to behaviour change: natural experimental study of the perception and use of new infrastructure to promote walking and cycling in local communities. BMJ Open; 03 September 2015

MRC Epidemiology Unit

MRC Epidemiology Unit